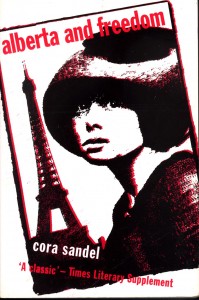

Extract > Alberta and Freedom

“Something she had witnessed had clothed itself in words in the secret recesses of her mind.”

Cora Sandel’s trilogy of Alberta novels has sadly fallen into obscurity. They are classics in every sense of the word, deserving of a much wider English readership. Read them and fall in love with Alberta. Read them and make room for Sandel on your bookshelf; she will become your favourite writer, and the Alberta trilogy your favourite books.

This extract is from Alberta and Freedom, the second in the trilogy. Alberta, now a young woman, is living on her own in Paris prior to the First World War.

The Alberta trilogy was translated into English by Elizabeth Rokkan (The Ice Palace).

La Villette St. Sulpice.

Past St. Germain-des-Près, across the Place St. Michel, over the Seine; La Cité, past Porte St. Martin, Gare-de l’Est; through broad and straight, narrow and crooked streets. Streets smelling of petrol, perfume, powder, and streets smelling of oil, chipped potatoes, pancakes. Regular, correct streets, where the houses stood looking just what they were; and others where signs, awnings, posters and advertisements of all kinds crowded each other, dissolving and displacing contours, charming away all underlying planes in a confusion of intricate pieces. Streets that buzzed with cheerful human life, while two rows of light-coloured treetops united in the far distant haze; and gloomy streets full of clammy shadow, clammy fate, something oppressive and uneasy that kept the sun away. Small parks, paradises gay with flowers and playing children; and the obscene horror of the slaughterhouse.

To plunge into it. To drift, wander about, watch, absorb it all. with no other purpose. To take one of the old-fashioned horse-buses, which still swayed along here and there – not the bright red motor-bus, which bustled about in certain streets. To dismount and take other buses, penetrate unknown territory, buy fruit from carts and eat it sitting on benches, hear the clock strike in different ways in different church towers and know that it didn’t matter, no-one knew where she was, no-one knew where she belonged. At the bar where she drank coffee and cracked a hard-boiled egg against the counter, she was someone who came and went and no-one could give any information about her. It made Alberta feel something approaching schadenfreude.

There was an outside seat on the horse-bus, nearest the coachman and just above the horses’ broad, pitching haunches. There you pitched high above everything too, you had a clear view.

Childhood tendencies are not easily escaped. They lead one further, lead one far. Alberta had had this inclination to drift since she was small. It could be roused by many things : tedium, weariness, physical unrest, a blue sky or a grey one, joy, an inexplicable impulse. It had acquired the addition of curiosity which did not make it any more permissible.

She could follow people unknown to her up and down streets, getting on and off the same means of transport with them to see where they finally went; listen intently to conversations between total strangers as if her whole existence depended on it; seek out places where she had no business to be, because some small feature gave her the feeling that something was happening there. Certain streets and houses had an inexplicable fascination for her; she drifted back to them time after time in order to stand there for a while, to watch people going out and in. Blindly unable to give herself any valid reason for it, she absorbed impressions as a sponge absorbs moisture.

She would return home from her expeditions tired, hungry, knowing that she had yet again used money, time and shoe leather to no purpose, and yet strangely satisfied, as if deep and mysterious demands in her had been pacified for a while. Her brain teemed with fragments of the conversations of strangers. Disconnected pictures of the teeming life of the streets succeeded each other, shutting out regret and uncomfortable thoughts.

If only that were all. But one night a little while later she would perhaps be sitting up with smarting eyes and feverish pulse, scribbling illegibly on paper torn with abandon out of the nearest exercise book, which would then be ruined.

Something she had witnessed had clothed itself in words in the secret recesses of her mind. Or remarks she had heard blazed up out of her memory, appearing to her like mysterious knots into which many threads of human life converged, entwined themselves and retreated into the obscurity from which they came. She wrote them down – and before she was aware of it, was engaged in a struggle with the language as if with a plastic material, trying to force life out of it as Eliel did with his clay. Reality lies hidden in outward occurrences, the words one hears are for the most part masked thoughts. But there are glimpses which enlighten, remarks which reveal. Alberta sometimes thought she had grasped something of it. And she fought with the recalcitrant words, they were like a mutinous flock tripping each other up. When they were eventually written down, conquered and in order, a lull fell in her mind after such unprofitable midnight turmoil.

In the morning something was there. It looked strange and unrecognizable, and belonged to some sequence, heaven alone knew what. It was blocked on all sides there was no way out in any direction. To find it she had to know more about life, much about life, everything possible about life and more than can be observed from the roof of a horse-bus. As the waterfall sucks and pulls, so can the teeming streets suck and pull. A yearning would seize her to swirl with it, if only to see what would happen, and a yearning to track down its myriads of secrets.

This business with little scraps of paper in the night-watches was another sore spot on Alberta’s conscience. The following day she would be dazed and incapacitated. And the pile of loose sheets in her trunk had been lying there for a long time, filling it up and making it untidy. They fluttered about in it indiscriminately. One day she would have to come to some decision about them. She could not be for ever opening it, slipping more into it, and shutting it again. But she had an unhappy weakness for this muddle of scribbled pages.

Buried in her memory there lay a fragmentary landscape. A shadow moved in it, appearing now here, now there, a naive figure making up poetry. The background shifted. It might be as unreal as a theatrical décor, a blue and gold mountain range, illuminated from below by an unnaturally low sun; it might be eddies in the current, a river eternally flowing, deep with grey upon grey or green upon green; a bank of snow in thaw beneath a light that was neither day nor night, neither winter nor summer. And it might be almost nothing, a dull speck in infinity, shut in by mist, rain, snowstorms, as by enormous draperies. The shadow was always the same, in an altered jacket of regrettable cut and with her hands tucked up inside her cuffs.

Like a piece of reality crystallized out of it all there once had existed a battered exercise book, filled with bad echoes of mediocre poets. It had come to light in the trunk one cold, raw winter afternoon in the Rue Delambre and turned out to be something to laugh and cry over, certainly not something to be found by anyone after one’s death; on the contrary. It became a hastily flaming, bright warmth, towards which Alberta held her ice-cold hands for a while, and to this extent it actually proved useful for an instant. Alberta did not like thinking about it.

One day the scraps in the trunk would have to go the same way.

Order your copy of Alberta and Freedom now.

This entry was posted in Extract and tagged Alberta, Cora Sandel, Elizabeth Rokkan, Feminism, Tracy Chevalier, Women in Translation. Bookmark the permalink.