Archive > Colquhoun the Artist

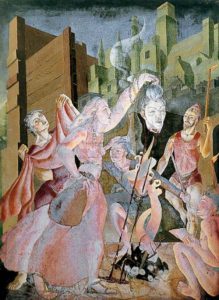

Colquhoun attended Cheltenham Ladies College and then enrolled at the local College of Art. She came to London in 1927 in order to study at the Slade School of Art. She was awarded joint first prize in the most prestigious of the Slade competitions, the Summer Composition Prize, in 1929 for a large oil painting Judith Showing the Head of Holofernes.

Her teacher, Professor Tonks, praised her ‘remarkable gifts’ and sense of design, but warned her, with some prescience, that:

‘the only danger in your development is that with your active and curious mind you may be led to run after all strange objects. You go out to gather strawberries and come back with two strange beetles and a spider instead.’

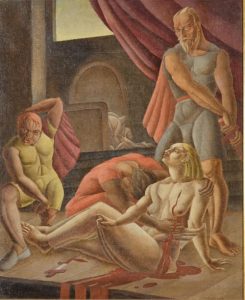

The Death of Lucretia by Ithell Colquhoun (1931)

Many of her paintings from this period were on classical or biblical themes. Judgement of Paris (1930) and Death of Lucretia (1931) are subjects that could have been tackled by artists at any time in the preceding three hundred years. However, although the subject matter was traditional, her interpretations were contemporary, frequently reversing and challenging traditional gender roles. Rather than providing an opportunity for the artist to paint voluptuous female flesh, the women in her paintings are powerful and assertive, never subservient. By contrast, her male figures are often indecisive, sometimes foolish. A number of her earlier paintings, such as Death of the Virgin (1931), were over six feet high. She wished to develop her skills in this direction and for three successive years, from 1931 to 1933, entered the competition for the Rome Scholarship in Mural Painting. Each time, however, she was unsuccessful. Some of the works that she submitted can be identified from inscriptions on the reverse. Mrs. Paul (c.1929) is one example.

After graduating from the Slade School of Art, Colquhoun spent some time travelling and studying abroad. Many of the 91 works that she exhibited at her first one-person show at Cheltenham, in 1936, consisted of drawings and watercolours of her travels through the Mediterranean.

Many of the works that she completed are topographical but there are also a number of domestic interiors. In these works Colquhoun gives early indications of a life-long interest in moments of change. Later, this would focus on change in the natural world or in spiritual states, but here it is more mundane. Human figures are always absent, but their recent traces remain, such as those left in a Bed in Greece.

Similarly, when she painted buildings, she concentrated on architectural features that hint at movement and transition, and what is psychologically telling, an absence of life. Beds are not made, clothes lie abandoned on chairs, windows are shuttered, doors are closed and gates fastened. High walls hem the viewer in (Gateway, 1937; Village Lane Corsica, 1937). There is no-one to be seen. Either Colquhoun has arrived late or the life that might have inhabited the studies has fled from her. The emptiness in these paintings is not benign; they provoke anxiety. They give rise to a sense of exclusion – a paradox in which the viewer feels rejected from the image under observation.

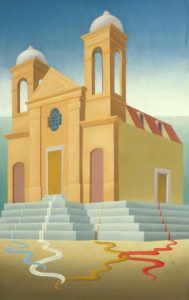

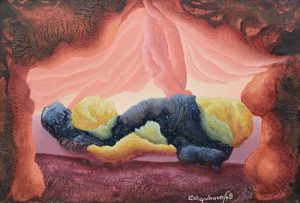

Rivières Tièdes, Ithell Colquhoun (1939)

This sinister quality culminates in the paintings of the Méditerranée series, in particular Rivières Tièdes (1939); that of a church, isolated and closed-up. The fascination with, and the horror of, emptiness surely has its origins in the artist’s own personal and emotional life and her endeavours to forge links with occult, artistic and literary groups that were so frequently thwarted. Her fate was to be an observer, seldom, and for long, a participant; and one can certainly read traces of this in The Crying of the Wind and in Peter Owen’s foreword to Goose of Hermogenes.

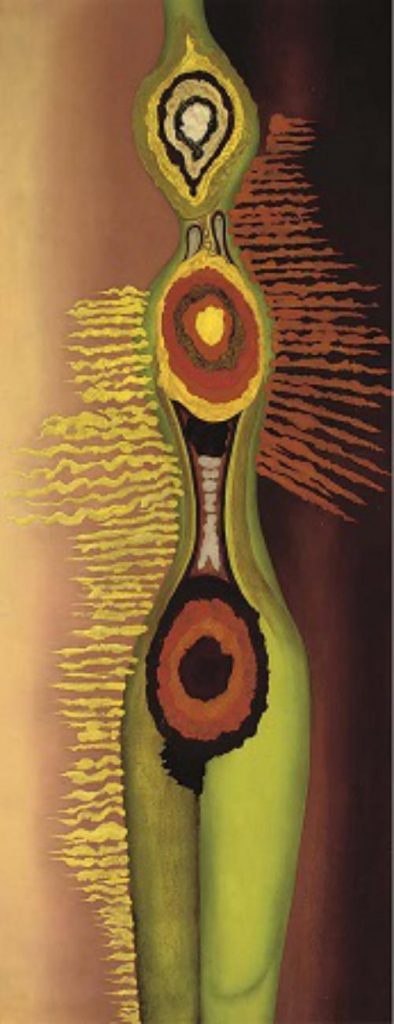

Scylla 1938 by Ithell Colquhoun 1906-1988 © Tate, London

Visits to Paris in the 1930s frequently exposed her to the work of Salvador Dalí and André Breton. In 1936, Colquhoun attended the International Surrealist exhibition held at the New Burlington Galleries in London. She was present at the famous lecture given by Salvador Dalí during which, dressed in a diving suit, he nearly suffocated. At that time, in the mid 1930s, he was fully engaged with his so called paranoiac-critical method, a mode of visual double entendre.

For a while, Dalí continued to be Colquhoun’s main stylistic influence and she produced a small number of paintings with a classical Dalínian double image, the most famous of which is Scylla (1938), currently in the Tate, inspired by what Colquhoun could see of her legs and lower torso whilst she was lying in the bath. Sardine and Eggs (c.1941) and Tree Anatomy (1942) are further examples of this visual ambiguity.

Surrealism and Colquhoun were a natural fit. To adopt the methods was to apply greater scrutiny of the subconscious, which extended beyond the mind to esoteric substrata, Occultism and alchemy. Colquhoun had from a young age shown interest and knowledge of all these facets of Surrealism. Despite in 1940 ceasing formal associations with the Surrealist Group in London (in fact she was informally banned after refusing to endorse the leader of the group, E.L.T. Mesens), she would regard herself as a surrealist all her life.

In the First Surrealist Manifesto (1924), surrealism was defined in terms of automatism:

SURREALISM: psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner, the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

For most artists, automatism was a two-stage process: the production of the initial marks using some method that relied on chance, followed by their modification, interpretation and elaboration, using a more conscious and controlled technical process. The word that best describes the second stage, the imaginative interpretation of the initial stimulus, is that it is an act of projection. Projection is a frequently used word in the contexts of alchemy and analytic psychology. Colquhoun was well aware of both these usages and refers to them extensively in her essays “The Mantic Stain” and the later expanded version “Children of the Mantic Stain” (which formed the basis for a 2016 Linder Sterling ballet).

The great majority of Colquhoun’s automatic works employ a technique known as Decalcomania. This is where paint is randomly applied to the canvas and then a second canvas squashed on top. What results, when peeled away from each other, is a messy mirror image. Following this it is up to the artist to delve within their psyche and reinterpret the paint. The effect can be quite arresting, as in Colquhoun’s Alcove’s:

Alcove I, Ithell Colquhoun (1946)

Alcove II, Ithell Colquhoun (1948)

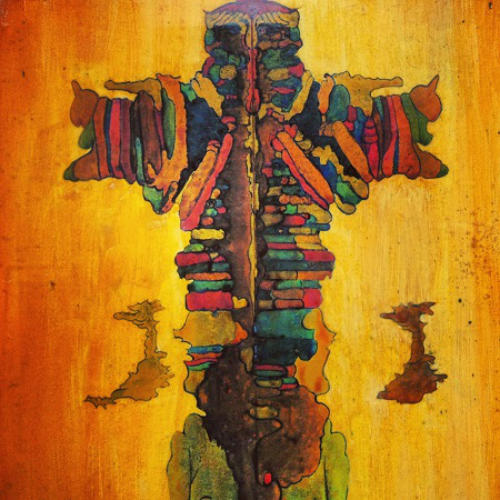

Horus, Ithell Colquhoun (c. 1957)

Other variations include Stillomancy, a technique developed by the Romanian Surrealist Dolfi Trost, in which the canvas is folded to create the mirror image, before the paint is worked …

Autumnal Equinox, Ithell Colquhoun (c. 1949), inspired by the wood graining of an old door, from which she made a rubbing.

… And Frottage, in which a canvas is placed above an uneven surface and the paint, chalk or pencil applied as to a stencil; much like the principles of brass rubbing.

Colquhoun went through a fever of activity as an artist during the ’60s and ’70s, first incorporating found materials into her work – a natural evolution from her work in Frottage – consisting mostly of packaging materials, such as egg cartons, polystyrene and cardboard boxes, which in her art were transformed from outer, disposable casing to the subject matter itself; an idea that followed quite literally the words of André Breton:

‘surreality would be embodied in reality itself and be neither superior nor exterior to it. And reciprocally, too, because the container would also be the contents.’

Materially her attentions wandered and between 1977 and 1979 she produced over 100 works in enamel paint. Her artistic preoccupations, however, remained the same. The metallic and earthy tones of enamel paint allowed Colquhoun to fully realise her interest in alchemical symbols and themes.

‘In these works she shows aspects of nature on local, global and cosmic scales. The images seem to originate from deep within the artist, but also in deep waters, deep space and remote time. They constitute a cosmology; images of great lyrical energy, power and delicacy, distilled from the artist’s private world. They mix the celestial with the earthly and the personal with the universal. Despite their small size, they appear to be boundless, the image capable of expanding infinitely in all directions. We can imagine her pouring, tilting and stirring the fast-drying paint with broad movements of arm and body. As she worked, we can almost hear her humming along to the music of the spheres.’ – Colquhoun biographer and art collector, Richard Shillitoe.

In the last decade of her life, at the height of this period in both enamel and alchemical and cosmic symbolism Colquhoun designed a quite spectacular pack of Tarot cards.

Ithell Colquhoun’s Tarot cards, work in enamel paint (1978)

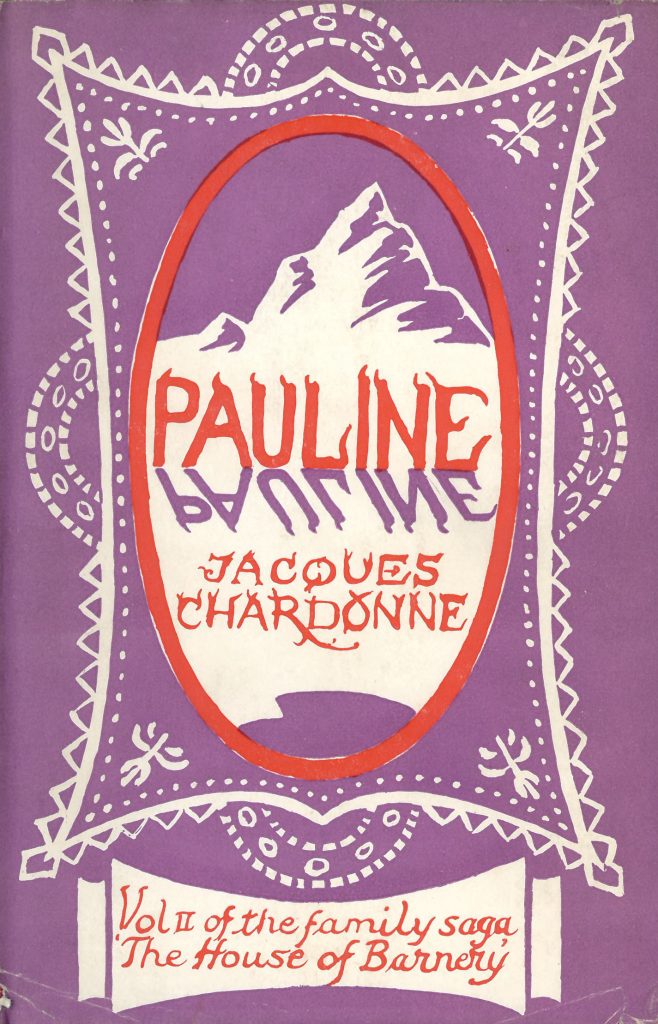

During her lifetime, Colquhoun designed four book jackets for the publisher Peter Owen.

Pauline: The Diary of an Epicure (1955)

Reminiscences of an Epicure by Francis Cunynghame (1955)

Writings of Edith Stein edited and translated by Hilda Graef (1956)

The Clothes of God: a Treatise on Neo-analytic Psychology by Alice Buck and Claude Palmer (1956)

She also designed the jackets to the original travelogues. We reproduced the frontispiece to fit our new editions:

This entry was posted in Archive, Authors, Extract and tagged Author Spotlight, Ithell Colquhoun, Richard Shillitoe, The Crying of the Wind: Ireland, The Living Stones: Cornwall. Bookmark the permalink.

Peter Owen is an independent British publisher founded in 1951 continuing the tradition of producing new and interesting writing.

Peter Owen, c/o Pushkin Press

Somerset House

Strand

London, WC2R 1LA

VAT Reg: 239952620

Registered Company no: 494915